If you remember the first book you finished all by yourself, you probably remember the feeling more than the plot: that little surge of pride, perhaps a buoyant realization you could go anywhere a story took you. That is the goal of the chapter book: to form a tailored, confidence-building bridge between picture books and the longer middle-grade novels to come.

What is a chapter book?

Chapter books are not just “books with chapters.” The term is a shortened form of first chapter books—stories written specifically for newly independent readers. These are children aged roughly 6–9 years, who are moving beyond simpler stories in early readers toward longer narratives. Chapter books feature short chapters, friendly page design, and an abundance of visual support, all calibrated to help a child read on their own and— hopefully!—want to do it again tomorrow.

A bridge by design

In recent years, publishers have invested heavily in this transitional space, building dedicated lines that sit between leveled readers and longer novels. Scholastic’s Acorn (for beginner readers) and Branches (early chapter books) are cases in point: purpose-built with short, self-contained chapters, approachable vocabulary, and illustrations on every page. The goal is to keep momentum strong and grow stamina without sacrificing fun.

[Newly independent] readers really need, want and deserve strong, complex storylines. We just need to be providing that content on their reading level.

Katie Carella, Scholastic Tweet

Katie Carella, Editorial Director of the Acorn and Branches imprints at Scholastic, speaks passionately about engaging readers in this age group. “[Newly independent] readers really need, want and deserve strong, complex storylines. We just need to be providing that content on their reading level.” She worries about the moment a child tries something too hard or too dull and decides, “I’m not a reader.” In her view, it’s essential to catch children during the small window of readiness.

Parents and educators also recognize the critical nature of seizing kids’ attention at this time of their development, contributing to the growth of the chapter book market. Expanding choice and appeal through a breadth of story topics that cater to different reading level abilities is key. The aim is not just to foster lifelong reading enjoyment, but to open up a child’s opportunities for long-term academic success.

These considerations are reflected in Scholastic’s Kids & Family Reading Report. The survey included reading habits— such as reading aloud and reading for fun—access to books, and the benefits of shared reading time as a parenting tool. Among the report’s findings was that 59% of parents surveyed reported using a children’s book to help their child process feelings or emotions. In addition to survey results, the report also includes age-specific tips parents can use to help improve their child’s reading skills.

What makes a chapter book “work”?

The most effective chapter books share several characteristics that reduce cognitive load while increasing engagement:

1. Stories that capture the reader

Learning to read is a challenge. That challenge is made more difficult if the books on offer don’t align with a reader’s interests. Fortunately, subject choice has grown significantly in the last twenty years and now encompasses a range of genres. Story arcs within a predictable framework, real stakes, concrete obstacles, and an earned resolution—delivered at a reading level that stretches but doesn’t deter—allow comprehension to “click”.

2. Shorter chapters

Chapters are bite-size—often just 6–10 pages long. While chapter length may vary throughout the book, a short first chapter is particularly important. The satisfaction and sense of achievement in finishing a chapter is key to building confidence in a newly independent reader. Armed with “I can do it” momentum, they can forge on with greater self-assurance. Engaging chapter books also typically end each chapter with a “cliff hanger” to entice the child into reading the next chapter.

Chapter book characteristics

- Stories that engage

- Shorter chapters

- Friendly page design

- Illustration and other visual support

- Series format

3. Pages that invite, not intimidate

Generous margins, open leading (the vertical space between each line of text), and larger type reduce the daunting impact of a text-heavy page. Fonts that are more rounded and less cramped also help the text appear less intimidating.

4. Illustrations that teach as they entertain

Beyond the classic full page or half page illustrations, the use of spot art, sequential (comic-style) panels, sound words emphasized in text, and speech bubbles all contribute to improving literacy skills. Rather than mere decoration or being used solely to reduce text on a page, these graphical elements form reading scaffolds that help build vocabulary, inference, comprehension, and stamina.

5. Series Continuity

Chapter books are most often published in series, and typically in non-sequential form. In large part, this is due to the transitional role they play: they’re necessarily short and more formulaic (relative to middle grade and YA) because readers gaining momentum need many books on tap.

Just as salient, there is the need for familiarity to diminish objections to starting a new book. It’s not unusual for a parent or teacher to feel like they’re a cross between a televangelist and a used car salesperson when pitching an unfamiliar book to a child in the 5-9 age group! With a series, however, familiar characters (who sometimes become dear friends), a known story rhythm, and running jokes provide a comforting framework, even with a new book. Children are generally keen to read all books in a series they enjoy —and can commence each book on a confident footing.

As Carella explains, “[series books] build fluency and stamina. After kids finish book one, they know they can read every book in that series. That’s why series publishing is key. It immediately builds confidence and familiarity [so that newly independent readers] can build their stamina and read faster.”

From picture-led to text-led — without losing anyone

Joe Cepeda laughs that when his son first started reading, he insisted on series books, declaring: “I only want to read it if there’s another one.” As a long-time illustrator-author of children’s books—both singular and in series— Cepeda has had plenty of time to contemplate the contribution images make to a narrative. His seasoned perspective on the interplay of text and images is frank: his job is not to echo the text, but to “surrender to the story,” taking care to match the age and imagination of a book’s audience.

“Chapter books and graphic novels [have] … certain mechanics that allow the script to take over” while at other times, the illustrations support the narrative “moment by moment.” Cepeda believes his job as an illustrator is to create images that enhance, harmonize and otherwise contribute creatively to the storytelling. In this way, he deepens the reader’s understanding of the text and appreciation for the story.

Graphic-forward texts and graphic novels make the architecture of a story visible for emerging readers, helping to build confidence, vocabulary, and endurance.

For parents and teachers, moving readers from fully illustrated picture books to text-heavier prose is a tricky proposition. This is where the “graphic toolkit” of chapter books has developed considerably. Where in the past a book was typically limited to one type of illustration, now there’s increasingly a mix. Hybrid pages may include cartoon speech balloons, decorative borders that cue mood, onomatopoeia set in display type, or even short panel sequences. As a result, graphic-forward texts and graphic novels make the architecture of a story more visible for emerging readers, helping to build confidence, vocabulary, and endurance.

Not all graphical elements are helpful, however. Eye-tracking studies with early readers show that when illustrations are streamlined and relevant, comprehension improves. However, when images are busy or contain extraneous details that distract beginners, attention scatters and recall drops. The takeaway for chapter books isn’t “less art,” it’s “intentional art.” In other words, pictures help most when they’re purposeful and guide attention to what matters: decoding the words and making meaning from the text.

Matching emerging readers with books

Montessori educators Mary Kern and Lori May (Montessori Children’s School, San Luis Obispo) describe what this looks like in practice. In mixed-age classrooms, they watch closely for the right balance of text and image for each child—not just by reading level, but by temperament. Some students need visual anchors to keep pages inviting; others find noisy layouts overwhelming.

They’ve also come to value graphic novels as legitimate literacy builders (Kern admits she was once a skeptic!), especially when paired with class routines that offer choice and spark curiosity. One method includes providing small tubs of genre-themed books to reduce the choice paralysis of library shelves, a technique adopted from the “The Book Whisperer” by Donalyn Miller.

May has observed that the design or text on a book cover can negatively influence its appeal. By wrapping selected books in brown paper sporting “just a few descriptors” she is often able to eliminate book-cover bias and help students delve into a story they ultimately enjoyed. With older elementary students, a simple plate stand that provides a prominent place where students can display a book recommendation for their peers has proven very popular. A contemporary’s opinion usually holds more sway than that of an adult!

On content, Kern and May agree that the increasing diversity of books and subject matter for the 6-9 age group has helped with snaring younger readers. But with one caveat: some series can become formula factories rather than maintaining narrative quality. They’d also love to see more science fiction that isn’t simply glib or silly, along with more accessible historical adventures at this level.

We need to give readers choices if we're going to reach every reader, because if we lose them at this very crucial point, it's often too late.

Katie Carella, Scholastic Tweet

At Scholastic, Carella is working hard to deliver quality content with enticing appeal. She believes the attraction of a popular series beyond a child’s current reading level can help draw them to something similar at an appropriate level. For example, Scholastic’s Dragon Masters series seeks to engage newly-independent readers until they’re ready for the popular middle-grade Wings of Fire series. The appeal is not just genre-related, but helps younger children feel part of an expanded reading coterie. As Carella explains, “We need to give readers choices if we’re going to reach every reader, because if we lose them at this very crucial point, it’s often too late.”

What's changed inside chapter books

Despite the dearth of science and history books lamented by Kern and May, today’s chapter books span a wider range of tones and topics compared with a generation ago. Apart from an abundance of humor and forays into the mildly disgusting, you’ll still find the classic school-and-friendship capers, and stories featuring magic, dragons, and mysteries —genres that are always catnip for 6–9-year-olds. In addition, there’s now accessible nonfiction, STEM-flavored problem-solving, slice-of-life realism, and gentle social-emotional themes.

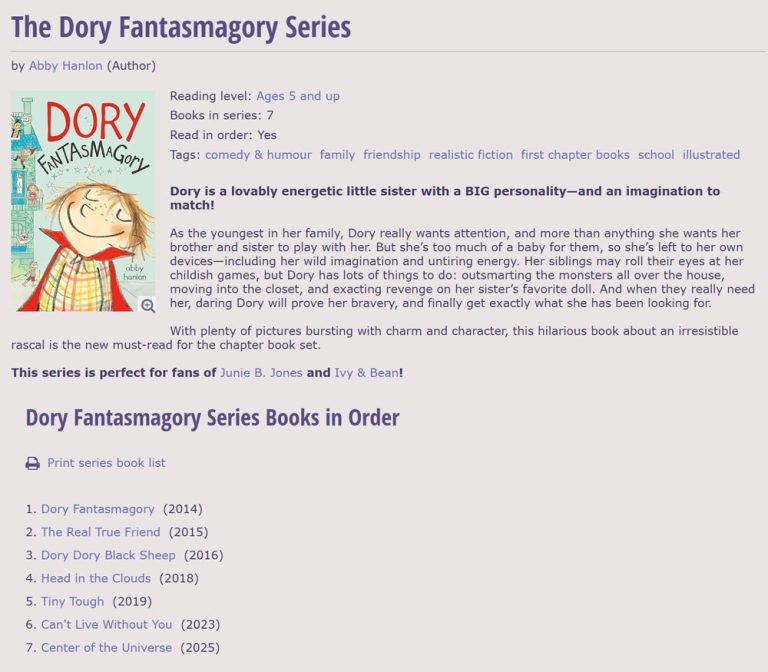

In style, there are hybrid formats that read like cartoons or diaries, and series that toggle between high-illustration and text-forward entries to match a reader’s growing stamina. Even popular and longstanding books continue to develop their illustration balance. Abby Hanlon’s Dory Fantasmagory, for example, helped codify the “heavily illustrated, voice-driven” chapter book with illustrations ranging from the more conventional to the voice bubble, while also including the cartoon scene format in more recent times.

Illustrators have adapted, too. Cepeda talks about “collaborating with the story,” which often means letting the script take the lead in chapter books—images carry emotion and clarify action but leave room for text to do the heavy lifting. For very newly independent readers, by contrast, the illustration may still do more narrative work. The art-text balance slides gradually as readers gain stamina—one reason kids (and parents and teachers) often adore series that evolve with them.

How this plays out at home (and at school)

This learning window for children aged 6-9 years is limited. It’s often the last quiet stretch before devices crowd the day and before the social swirl of later primary years makes leisure reading harder to protect. A few practical patterns can help optimize this critical time in a child’s reading development:

- Bedtime as homework in disguise. One chapter aloud each night is the perfect shared reading time. With a chapter book, there’s last night’s cliffhanger, tonight’s adventure, and tomorrow’s prediction. As confidence grows, many children quietly flip roles—finishing the next chapter themselves because they can’t wait to know what happens next!

- Match the page to the child. If a book looks daunting, it will feel daunting. For a wobbly reader, start with shorter first chapters, generous white space, and frequent artwork. For a child who’s ready to stretch, nudge into slightly denser pages—but make sure it’s not at the expense of continued motivation.

- Let humor lead. Kern and May point out that message-heavy stories can pile on cognitive and emotional load for this age; there is plenty of time for that later. Laughter keeps pages turning; practice and enjoyment are the elements to building lifelong readers .

- A note about quality. Parents sometimes worry that a silly series isn’t “serious” enough. Montessori School’s Lori May has a view which is refreshingly pragmatic: while there are times to curate closely, if a book is age-appropriate and keeps a hesitant reader reading, that momentum is gold.

- Use peers as booksellers. Montessori classrooms crack this code elegantly with student book talks and the “my personal recommendation” plate stand. At home, you can borrow the idea: invite a friend to bring a favorite book or series and “sell” it over snacks.

Chapter books rising

In the last two decades, chapter books have evolved to become more than mechanical texts kids labor through before reaching the proficiency for middle-grade novels. Increasing efforts to engage and support the emerging reader have contributed to chapter books that blend design, illustration, and story architecture to lower reading barriers and capture children’s imagination. Instrumental to this process is the prime role that series books play in maximizing reading appeal and minimizing a child’s resistance to starting a new book.

Many thanks to Mary Kern, Lori May and Joe Cepeda for taking the time to discuss their work with me, and to Katie Carella for her insightful seminar and comments.

Tips for parents

- Avoid comparisons with other children’s reading fluency or book choices.

- Book trailers are short (30-60 sec) introductions to a given book or series—the equivalent of the text blurb on the back—and can help engage a reluctant reader. [See a list of book trailers here.]

- Not all chapter books and early readers are the same. Look inside at the balance of text and illustrations and consider what best suits your child.

- Be prepared and have the next book in a series or a recommendation ready so as not to lose momentum.

- Rather than excessive praise, consider a good conversation about the book. If possible, read the book yourself. If not, prepare some leading questions that involve more than “yes or no” answers.

- Read yourself! Ideally a physical book, magazine or newspaper, or a dedicated e-reader (to delineate from general phone/device time). Modeling yourself as a reader within the home doesn’t have to involve a tome or literary classic.

- Be mindful how you talk about yourself as a reader (“I don’t read much”, “I’m not a reader”, “I should read more”) —your young reader is listening and modeling themselves on what you say.

Explore chapter book series by age or genre

- Continuity provides powerful leverage when encouraging younger readers. It’s no surprise then, that books in this age group are overwhelmingly books in series—as a glance at the shelves in a library or bookshop will confirm. Carella makes the same case from the publisher side: series “build fluency and stamina”; after a child finishes book one, they know they can read the rest—and that confidence compounds.

- To avoid the paralysis of too much choice, start with your child’s personality then explore one or two of their interests. On the Cereal Readers website there are a many ways to search, including single genre, reading age, or a combination of age and multiple genres.